This report summarizes U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement's (ICE) Enforcement and Removal Operations (ERO) Fiscal Year (FY) 2016 removal activities. ICE shares responsibility for enforcing the nation's immigration laws with U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). In executing its enforcement duties, ERO focuses on two core missions: 1) the identification and apprehension of criminal aliens and other priority aliens located in the United States; and 2) the detention and removal of aliens arrested in the interior of the United States as well as those interdicted by CBP at the nation's borders. ICE is committed to smart immigration enforcement, preventing terrorism, and combatting the illegal movement of people and goods.

This report analyzes ICE ERO's FY 2016 removal statistics to demonstrate the impact of the Department of Homeland Security's (DHS) enforcement priorities. In executing its responsibilities, ICE has continued prioritizing its limited resources on the identification and removal of threats to national security, border security, and public safety, as outlined in Secretary of Homeland Security Jeh Johnson's November 20, 2014 memorandum titled Policies for the Apprehension, Detention and Removal of Undocumented Immigrants.

The nature and scope of ICE's civil immigration enforcement is impacted by a number of factors, including: 1) the level of cooperation from state and local law enforcement partners; 2) the level of illegal immigration; and 3) changing migrant demographics.

DHS's clearer and more refined Civil Immigration Enforcement Priorities,[1] which ICE began implementing in FY 2015, place increased emphasis and focus on the removal of convicted felons and other public safety threats over non-criminals. ICE continued the implementation of these priorities with steady success during FY 2016. The implementation of the Priority Enforcement Program (PEP) further builds on the prioritization for removal of convicted criminals with the support of state and local jurisdictions. PEP became fully operational in July 2015, and, since that time, ICE has engaged in extensive efforts to encourage state and local law enforcement partners to collaborate with ICE to ensure the transfer and removal of serious public safety threats.

ICE conducted more removals in FY 2016 than in FY 2015 due to a combination of increased state and local cooperation through PEP and increased border interdictions by CBP. As detailed below, ICE's targeted focus on the most significant threats to national security, public safety, and border security has meant that criminals and other priorities account for a high share of removals.[2] In fact, 99.3 percent of aliens ICE removed in FY 2016 clearly met DHS' enforcement priorities. ICE also continues to focus on criminal aliens, as 58 percent of overall ICE removals, including 92 percent of ICE removals initiated in the interior of the country, were of convicted criminals. At the same time, 95 percent of non-criminal removals were apprehended at or near the border or ports of entry. As ICE continued its implementation of the Department's enforcement priorities during FY 2016 and state and local cooperation increased, ICE saw continued progress in ensuring its resources are appropriately focused on keeping the nation safe and secure.

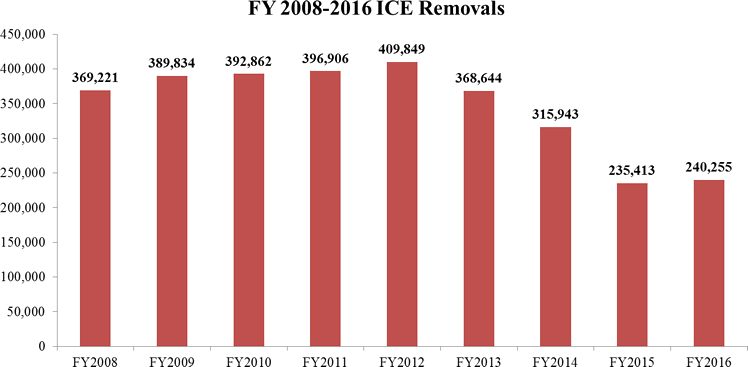

Total ICE Removals

ICE removed a total of 240,255 aliens in FY 2016, a two percent increase over FY 2015, but a 24 percent decrease from FY 2014. The following sections of this report identify a number of factors that have contributed to the decrease in removals from previous years.

Figure 1

Note: ICE removals include removals and returns where aliens were turned over to ICE for removal efforts.

Removals Overview

- ICE conducted 240,255 removals.

- ICE conducted 65,332 removals of individuals apprehended by ICE officers (i.e., interior removals) (Figure 5).

- 60,318 (92 percent) of all interior removals were previously convicted of a crime.

- ICE conducted 174,923 removals of individuals apprehended at or near the border or ports of entry.[3]

- 58 percent of all ICE removals, or 138,669, were previously convicted of a crime.

- ICE conducted 60,318 interior criminal removals.

- ICE removed 78,351 criminals apprehended at or near the border or ports of entry.

- 99.3 percent of all ICE FY 2016 removals, or 238,466, met one or more of ICE’s stated civil immigration enforcement priorities.[4]

- Of the 101,586 aliens removed who had no criminal conviction, 95 percent, or 96,572, were apprehended at or near the border or ports of entry.[5]

- The leading countries of origin for removals were Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador.

- 2,057 aliens removed by ICE were classified as suspected or confirmed gang members.

Figure 5

Conclusion

Over the course of FY 2016, ICE has continued to improve its ability to target individuals who threaten public safety, national security, and border security as demonstrated by the fact that 99.3 percent of individuals that ICE removed met ICE’s civil immigration enforcement priorities. This represents an increase from FY 2015. As ICE’s enforcement operations continue to align with the Department’s civil enforcement priorities, and state and local cooperation increases, ICE expects continued progress in ensuring its resources are appropriately focused in keeping the nation safe and secure.

Definitions of Key Terms

Arrest: An arrest, also called an apprehension, is defined as the “act of detaining an individual by legal authority based on an alleged violation of the law.”

Border Removal: An individual removed by ICE who is apprehended by a CBP officer or agent while attempting to illicitly enter the United States at or between the ports of entry. These individuals are also referred to as recent border crossers.

Convicted Criminal: An individual convicted in the United States for one or more criminal offenses. This does not include civil traffic offenses.

Immigration Fugitives: An individual who has failed to leave the United States based on a final order of removal, deportation, or exclusion, or has failed to report to ICE after receiving notice to do so.

Intake: An intake is the first book-in into an ICE detention facility associated with a unique detention stay. This does not include transfers between ICE facilities.

Interior Removal: An individual removed by ICE who is identified or apprehended in the United States by an ICE officer or agent. This category excludes those apprehended at the immediate border while attempting to unlawfully enter the United States.

Other Removable Alien: An individual who is not a confirmed convicted criminal, recent border crosser or other ICE civil enforcement priority category. This category may include individuals removed on national security grounds or for general immigration violations.

Previously Removed Alien: An individual previously removed or returned who has re-entered the country illegally.

Reinstatement of prior Removal Order: The removal of an alien based on the reinstatement of a prior removal order, where the alien departed the United States under an order of removal and illegally reentered the United States (INA § 241(a)(5)). The alien may be removed without a hearing before an immigration court.

Removal: The compulsory and confirmed movement of an inadmissible or deportable alien out of the United States based on an order of removal. An individual who is removed may have administrative or criminal consequences placed on subsequent reentry because of the removal. ICE removals include removals and returns where aliens were turned over to ICE for removal efforts.

Return: The confirmed movement of a potentially inadmissible or deportable alien out of the United States not based on an order of removal, but through either voluntary departure, voluntary return, or withdrawal under docket control.

[1] See Appendix C for a detailed description of Civil Immigration Enforcement Priorities and sub-priorities return to text

[2] See Appendix B for key terms and definitions | return to text

[3] Approximately 94 percent of these individuals were apprehended by U.S. Border Patrol agents and then processed, detained, and removed by ICE. The remaining individuals were apprehended by CBP officers at ports of entry. | return to text

[4] As defined in the March 2011 ICE Memorandum: Civil Immigration Enforcement: Priorities for the Apprehension, Detention, and Removal of Aliens | return to text

[5] ICE defines criminality via a recorded criminal conviction obtained by ICE officers and agents from certified criminal history repositories. The individuals described above include recent border crossers, fugitives from the immigration courts, and repeat immigration violators | return to text

Impact

Impact of Civil Immigration Enforcement Priorities

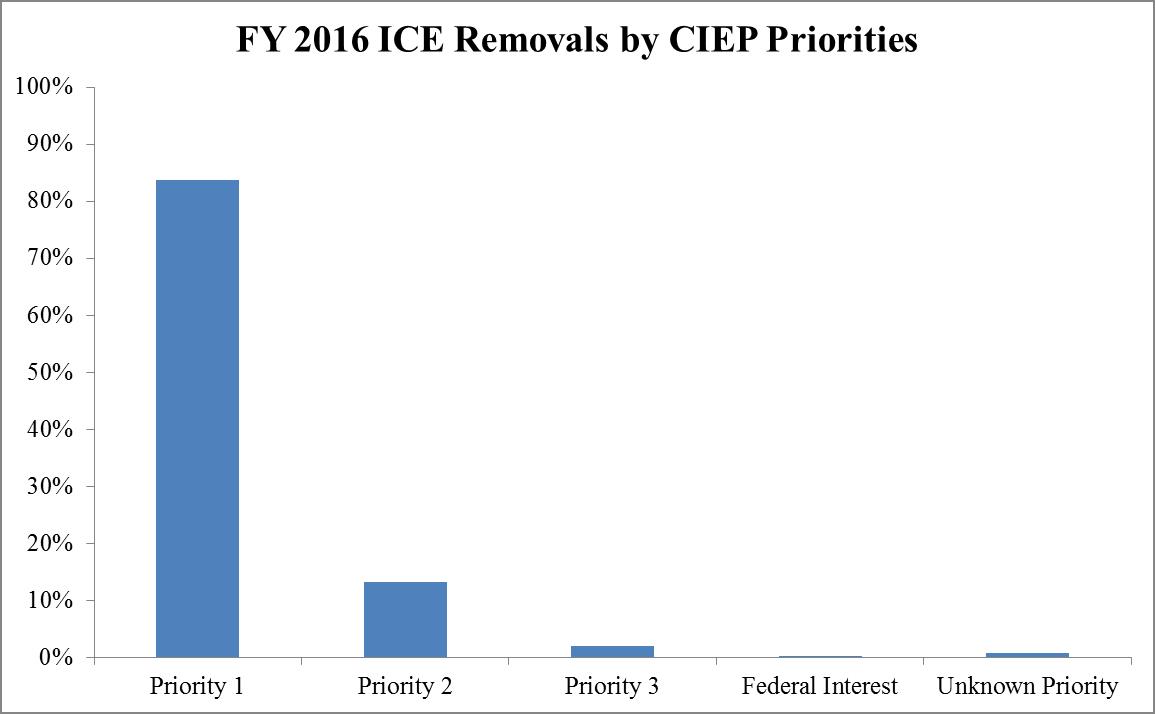

FY 2016 marked continued progress in ICE's implementation of revised Department-wide immigration enforcement priorities, as directed by Secretary Johnson in his November 20, 2014, memorandum, Policies for the Apprehension, Detention, and Removal of Undocumented Immigrants known as the Civil Immigration Enforcement Priorities (CIEP). The priorities have intensified ICE's focus on removing aliens convicted of serious crimes, public safety and national security threats, and recent border entrants.

More specifically, DHS's priorities establish three civil immigration enforcement categories, in descending order of priority. These priorities are: 1) national security threats, convicted felons or "aggravated felons," criminal gang participants, and illegal entrants apprehended at the border; 2) individuals convicted of significant or multiple misdemeanors, or individuals apprehended in the U.S. interior who unlawfully entered or reentered this country and have not been continuously and physically present in the United States since January 1, 2014, or individuals who have significantly abused the visa or visa waiver programs; and 3) individuals who have failed to abide by a final order of removal issued on or after January 1, 2014. ICE may also include individuals not falling within the aforementioned categories if their removal would serve an important federal interest.

Since these priorities went into effect during FY 2015, FY 2016 was the first full year of implementation. ICE's FY 2016 removal statistics in Table 1 below, broken out by CIEP Priority Status, demonstrate continued strong alignment to these revised priorities. In FY 2016, 99.3 percent of total ICE removals were individuals who were clearly a CIEP priority, and 83.7 percent were Priority 1 aliens.

| Priority 1 | Priority 2 | Priority 3 | Federal Interest | Total with a CIEP Priority | Unknown Priority | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 201,020 | 31,936 | 4,952 | 558 | 238,466 | 1,789 | 240,255 |

| 83.7% | 13.3% | 2.1% | 0.2% | 99.3% | 0.7% | 100% |

This alignment with the CIEP Priorities, shown in Figure 2, exemplifies ICE’s continued focus on targeted enforcement during FY 2016.

Figure 2

Focus

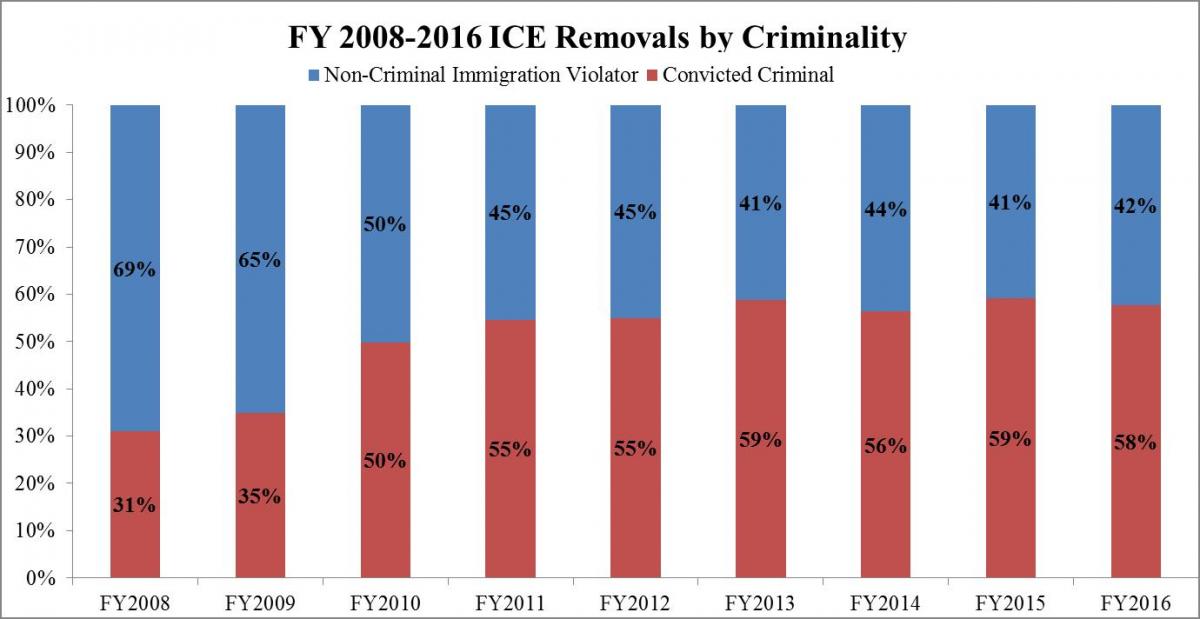

Focus on Convicted Criminal Aliens

ICE has continued to focus on identifying, arresting, and removing convicted criminals in prisons and jails, and through at-large arrests in the interior, as demonstrated by its removal statistics. In FY 2016, ICE sustained the quality of its removals from previous years by continuing to focus on serious public safety and national security threats. Of all ICE removals, 138,669, or 58 percent, were convicted criminals. This proportion is up from 31 percent in FY 2008 (see Figure 3). And 77.6 percent of removals of convicted criminals were ICE’s highest priority, CIEP Priority 1.

Figure 3

ICE’s interior operations were complicated by the ruling of the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals in Rodriguez v. Robbins, 715 F.3d 1127 (9th Cir. 2013). Under Rodriguez, individuals who previously would have been detained without bond may seek release on bonds from immigration judges. Their cases are then transferred from the relatively expedited detained court docket to the slower non-detained court docket, thereby decreasing the number of overall removals in a given year. This Rodriguez decision applies throughout the Ninth Circuit, the federal court jurisdiction with the largest number of individuals in removal proceedings

Removals

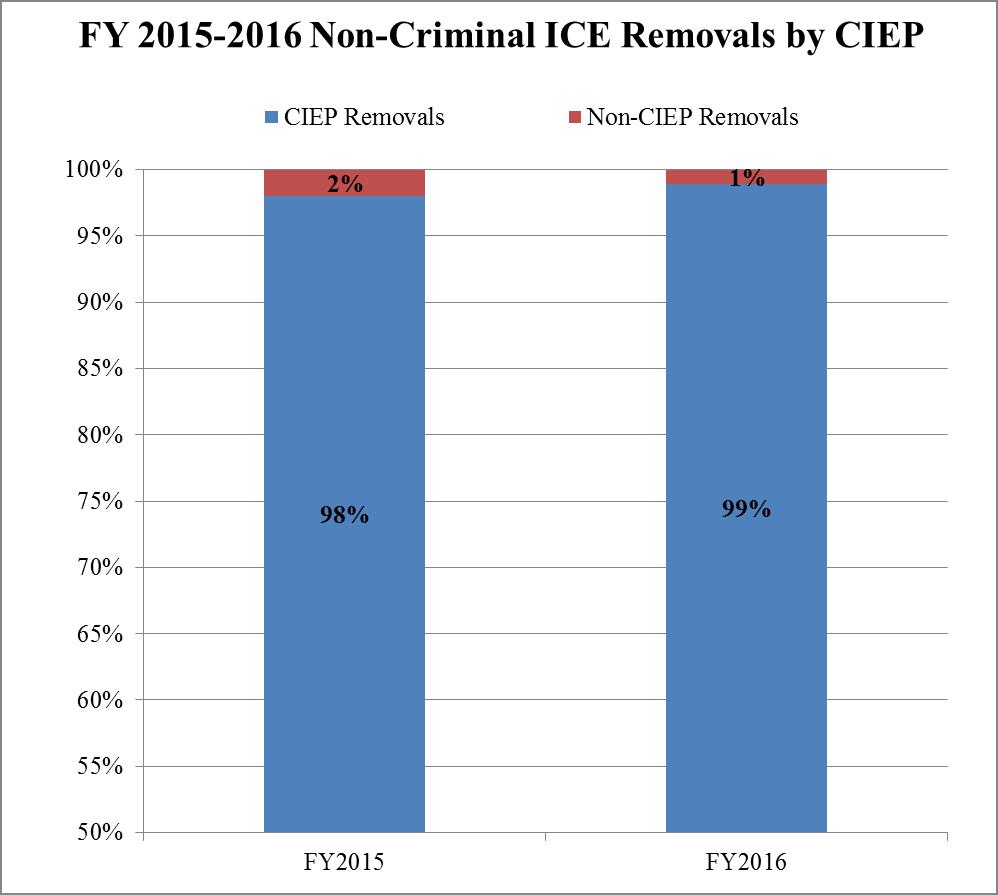

Non-Criminal Removals

The great majority (95 percent) of ICE removals of non-criminal immigration violators were individuals encountered by CBP agents and officers at or near the border or ports of entry. Significantly, 99 percent (100,475 out of 101,586) of ICE’s non-criminal removals clearly met one of DHS’ enforcement priorities, a further improvement from already high levels in FY 2015 (see Figure 4).

Figure 4

Interior Removals

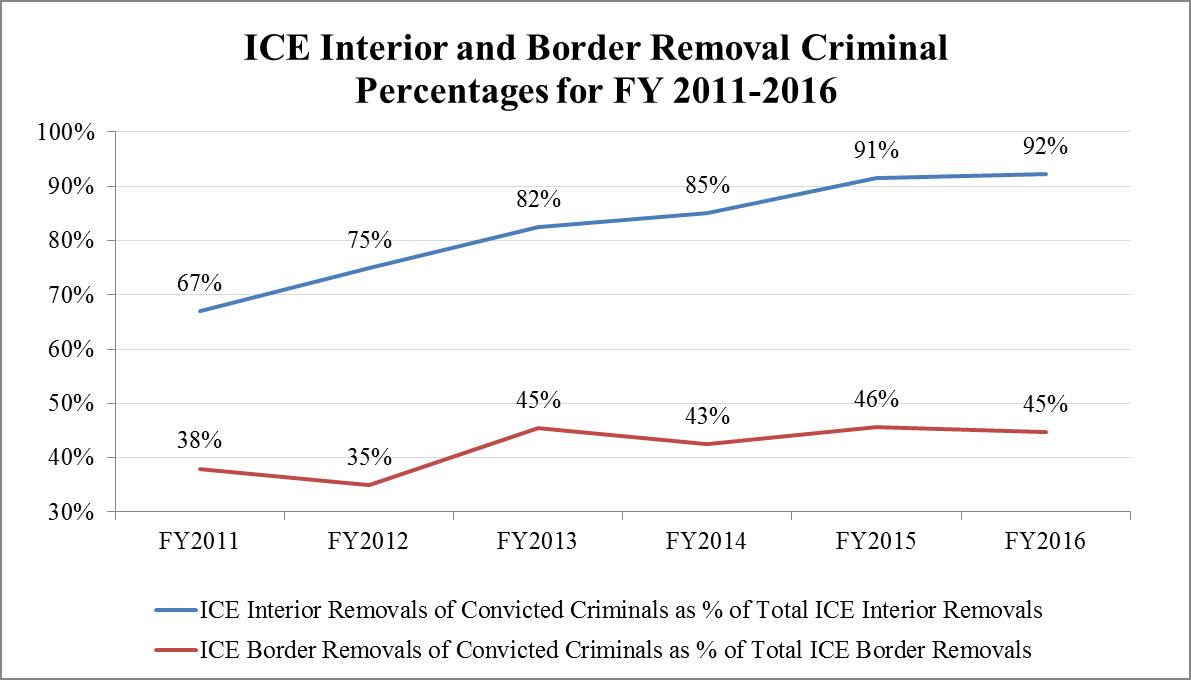

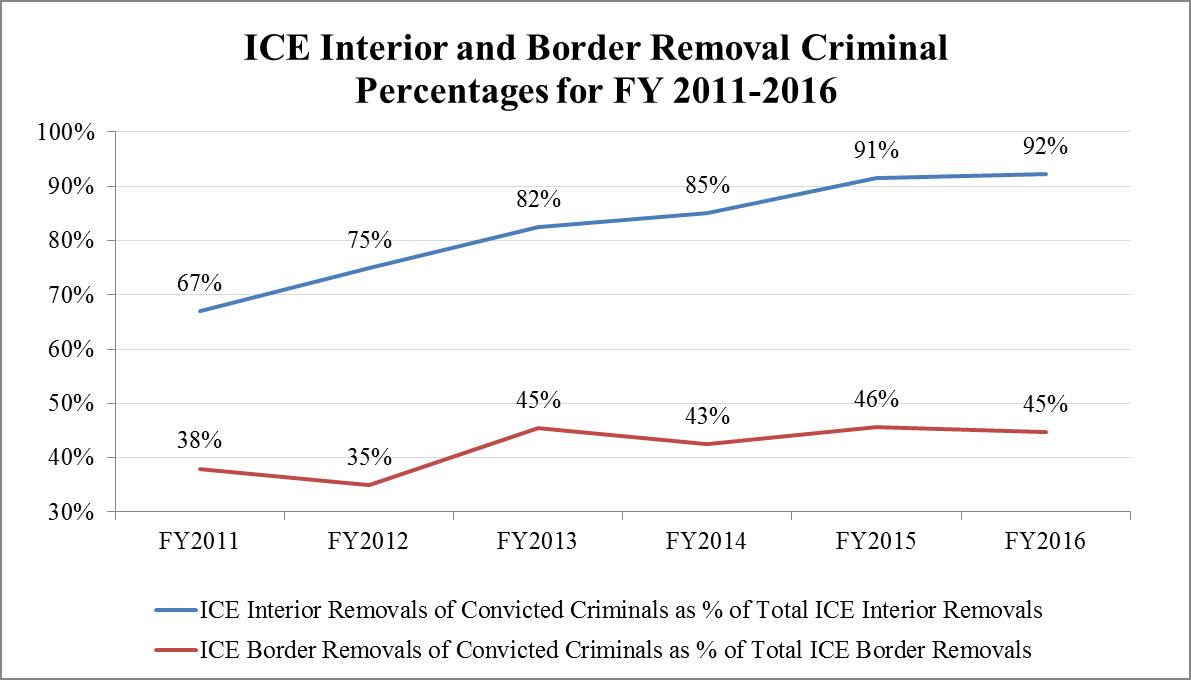

In addition to the high overall percentage of ICE removals that were of convicted criminals, ERO’s interior enforcement activities have led to a sharp increase since 2011 in the percentage of ICE’s interior removals (i.e., individuals apprehended by ICE officers and agents in the interior) that were of convicted criminals. As shown in Figure 5, this percentage continues to trend upward, from 67 percent in FY 2011 to 92 percent (60,318 out of 65,332) in FY 2016. Border removals in this figure include aliens apprehended at the border by the U.S. Border Patrol (USBP) and subsequently repatriated by ERO.

Figure 5

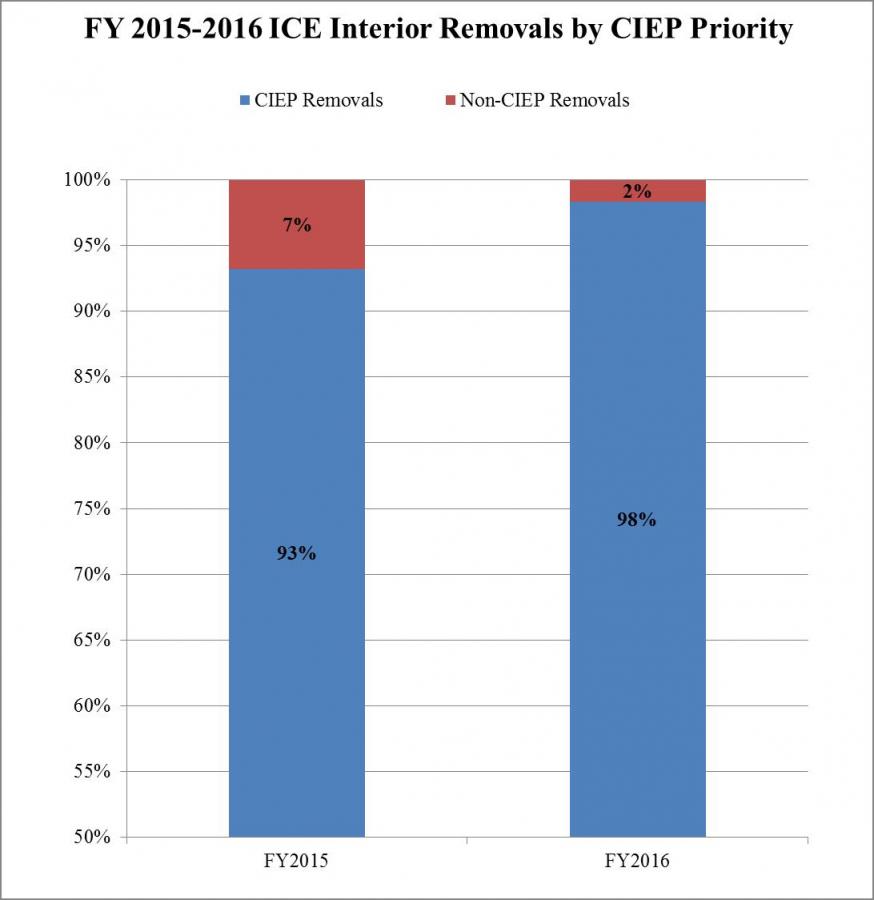

Figure 6

ICE conducted 65,332 interior removals in FY 2016, with 98.3 percent of them clearly falling into one of the CIEP priorities, as shown in Figure 6. This figure represents an increase of 5 percentage points over the proportion of interior removals that were CIEP priories in FY 2015.

Partners

Cooperation from State and Local Law Enforcement Partners

The enactment of numerous state statutes and local ordinances reducing and/or preventing cooperation with ICE, in addition to federal court decisions which created liability concerns for cooperating law enforcement agencies, led an increasing number of jurisdictions to decline to honor immigration detainers before implementation of PEP in July 2015. Despite improvement following PEP implementation, ERO documented a total of 21,205 declined detainers in 567 counties in 48 states including the District of Columbia between January 1, 2014, and September 30, 2016. Declined detainers result in convicted criminals being released back into U.S. communities with the potential to re-offend, notwithstanding ICE’s requests for transfer of those individuals. Moreover, these releases constrain ICE’s civil immigration enforcement efforts because they required ICE to expend additional resources to locate and arrest convicted criminals who were at-large rather than transferred directly from jails into ICE custody, drawing resources away from other ICE enforcement efforts.

In July 2015, following implementation of PEP, ICE began using revised forms, the I-247D detainer form and the I-247N, a request for notification form. In addition to the I-247D and I-247N, in late 2015 ICE began using the I-247X immigration detainer form, which applies to non-PEP priority subcategories, and which ICE may use to seek custody transfers from cooperative jurisdictions. Each of the 24 ICE Field Office Directors whose areas of responsibility includes at least one location that does not honor detainers are in ongoing discussions with their law enforcement partners in order to tailor PEP in each location to best meet the needs of their communities.

Additionally, to facilitate state and local cooperation, Secretary Johnson, then-Deputy Secretary Mayorkas, and Director Saldaña met with elected and law enforcement officials in some of the nation's largest jurisdictions. DHS and ICE officials also regularly engage with senior law enforcement officials from across the nation through various associations and task forces. This robust engagement is producing results. Counties like Los Angeles, Alameda, Fresno, San Mateo, Sonoma, and Monterey in California and Miami-Dade in Florida are now working with ICE through PEP. Today, many law enforcement agencies, including previously uncooperative jurisdictions, are now cooperating with ICE through PEP as ICE Field Office Directors continue to strengthen and improve relationships with their local law enforcement partners.

As a result of ICE’s efforts, declined detainers have dropped significantly over the past fiscal year. In FY 2016, ERO documented a 77 percent drop in declined requests for transfer (from 8,542 in FY 2015 to 1,970 in FY 2016) as well as a 29 percent drop in the number of counties declining detainers (395 counties in FY 2015, versus 279 counties in FY 2016). ERO attributes this improvement to increased local law enforcement agency cooperation as a result of PEP, and more selective and targeted issuance of detainers that align more closely to prioritized populations.

Apprehensions

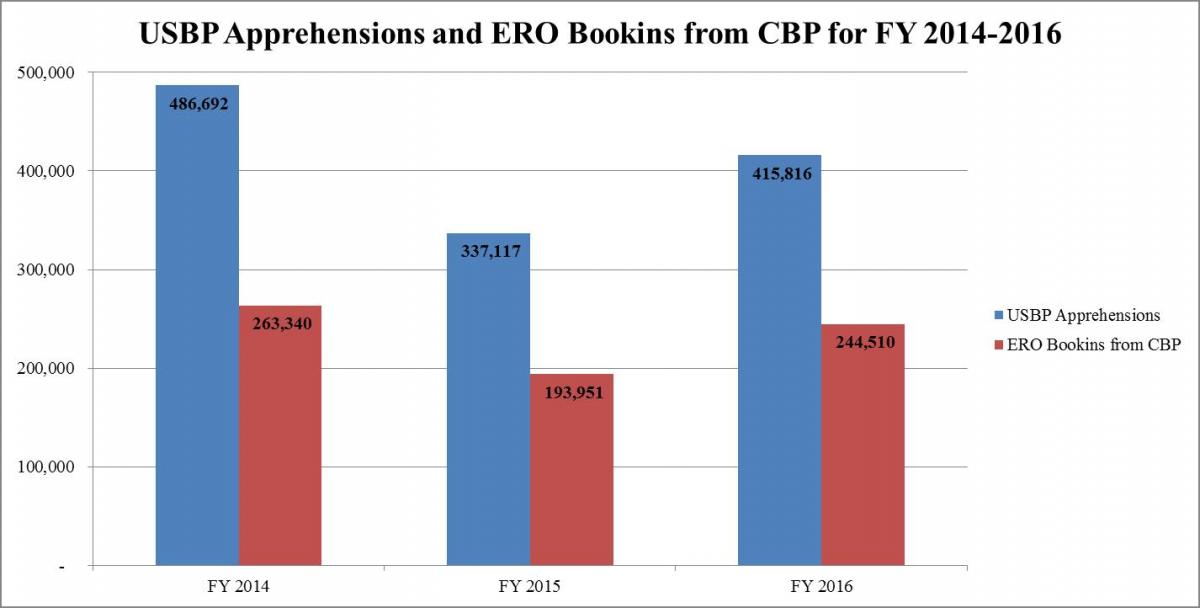

Increased Illegal Migration and CBP Apprehensions

ICE supports border security efforts by detaining and removing certain individuals interdicted by CBP at the border and elsewhere. Historically, a large share of ICE’s removals have been based on CBP’s border apprehensions. In FY 2016, the Border Patrol apprehended 415,816 people, an increase of 23 percent from FY 2015 as shown in Figure 7. This in turn resulted in an increase in overall FY 2016 ICE intakes based upon those CBP apprehensions, rising 26 percent from 193,951 intakes in FY 2015 to 244,510 intakes in FY 2016.

Figure 7

Source: USBP apprehension data as provided by USBP; figures may not match USBP year-end statistics

Demographics

Changing Migrant Demographics

Changing migrant demographics also continued to impact ICE removal operations in FY 2016, as illegal entries by Mexicans continued to decrease while those by Central Americans continued to increase. More time, personnel resources, and funding are required to complete the removal process for nationals from Central America and other non-contiguous countries as compared to Mexican nationals apprehended at the border. These costs have increased because removals of non-Mexican nationals require ICE to use additional detention capacity, more time and effort to secure travel documents from the host country, and to arrange air transportation to remove the individual to the home country.

Additionally, many Central American nationals are asserting claims of credible or reasonable fear of persecution. A total of 101,639 aliens made defensive asylum claims in FY 2016, up from fewer than 60,000 in each of the previous two fiscal years. Asylum cases require additional adjudication, and therefore, take longer to process and consume more ERO resources than certain other cases on ICE’s docket.

Methodology

Data Source

Data used to report ICE statistics are obtained through the ICE Integrated Decision Support (IIDS) system data warehouse.

Data Run Dates

- FY 2016: IIDSv1.22.1 run date 10/04/2016; ENFORCE Integrated Database (EID) as of 10/02/2016

- FY 2015: IIDSv1.19 run date 10/04/2015; ENFORCE Integrated Database (EID) as of 10/02/2015

- FY 2014: IIDS v1.16 run date 10/05/2014; EID as of 10/03/2014

- FY 2013: IIDS v1.14 run date 10/06/2013; EID as of 10/04/2013

- FY 2012: IIDS v1.12 run date 10/07/2012; EID as of 10/05/2012

- FY 2011: IIDS run date 10/07/2011; EID as of 10/05/2011

- FY 2010: IIDS run date 10/05/2010; EID as of 10/03/2010

- FY 2009: Removals and Returns are an adjusted historical number of an IIDS run date of 8/16/2010 (EID as of 8/14/10) and will remain static.

Removals

Removals include removals and returns where aliens were turned over to ICE for removal efforts. Removals data are historical and remain static. Returns include Voluntary Returns, Voluntary Departures, and Withdrawals Under Docket Control.

In FY 2009, ICE began to “lock” removal statistics on October 5 at the end of each fiscal year, and counted only aliens whose removal or return was already confirmed. Aliens removed or returned in that fiscal year but not confirmed until after October 5 were excluded from the locked data, and thus from ICE statistics. To ensure an accurate and complete representation of all removals and returns, ICE will count removals and returns confirmed after October 5 toward the next fiscal year. FY 2012 removals, excluding FY 2011 “lag,” were 402,919. FY 2013 removals, excluding FY 2012 “lag,” were 363,144. FY 2014 removals, excluding FY 2013 “lag,” were 311,111. FY 2015 removals, excluding FY 2014 “lag,” were 231,250. FY 2016 removals, excluding FY 2015 “lag,” were 235,524.

Any voluntary return on or after June 1, 2013 without an ICE intake case will not be recorded as an ICE removal.

ERO Removals include aliens processed for Expedited Removal (ER) and turned over to ERO for detention. Aliens processed for ER and not detained by ERO are primarily processed by Border Patrol. CBP should be contacted for those statistics.

FY 2012 – FY 2013 Removals include ATEP removals.

Criminality

Criminality is determined by the existence of a criminal conviction.